Recovering Food Narratives – Stories from Western Avadh

Diets in western Avadh (Uttar Pradesh, India), today, mainly consist of roti (made of wheat), highly polished rice, potatoes, sugar, tea, and processed foods like biscuits. Protein-rich foods like dairy, pulses, fish and meat have become an occasional delicacy for most families.

Is this how diets have always been in this region? What did people eat in the past? 30-40 years ago, before the Green Revolution? How have diets changed? How are these changes linked to changes in land, policy and power structures? Have some foods disappeared? What about the knowledge of processing, cooking and recipes? How have people of different classes, castes or religions experienced these changes? Want to know more?

Click on any icon in the food mat below.

Inside each icon, you will see a timeline on the right side that gives you a snapshot of major changes influencing a particular food group or category. The infocards on the left can be searched by geography, social category and season: they contain primary source material such as videos, quotations from informants in the field, textual material from gazetteers and other historical records, and graphs made using government survey data.

This portal draws upon the findings of a three year multidisciplinary study on food and farming transitions in western Avadh. Want to know more about the research? Click Here.

जमीन और खान-पान की कहानियाँ - पश्चिमी अवध के अनुभव

पश्चिमी अवध में आज अधिकतर लोग सिर्फ गेहूं की रोटी, सफेद चावल, आलू, चाय, चीनी और बाजारी पदार्थ, जैसे बिस्किट और रस्क, खा रहे है। सिर्फ कुछ ही परिवार दाल, दुग्ध पदार्थ, अण्डा या मीट-मछली रोज़ खा पा रहे हैं – बाकी सब के लिये यह कभी-कभी खाने वाले चीज़ हो गई हैं। लेकिन 30-40 साल पहले खान-पान कैसा था, और यह कैसे बदला? यह बदलाव कृषि, नीति और सामाजिक नर्गीकरण से कैसे जुड़े है?

‘खेती, खाना और पोषण के रिश्ते’ नामक अध्ययन से मिली जानकारियाँ इस पोर्टल पर उपलब्ध हैं। विस्तार से जानने के लिये नीचे चटाई पर कोई भी चीज़ पर क्लिक कीजिये । अध्ययन के बारे में समझने के लिये यहां क्लिक कीजिये।

Transitions in food and farming

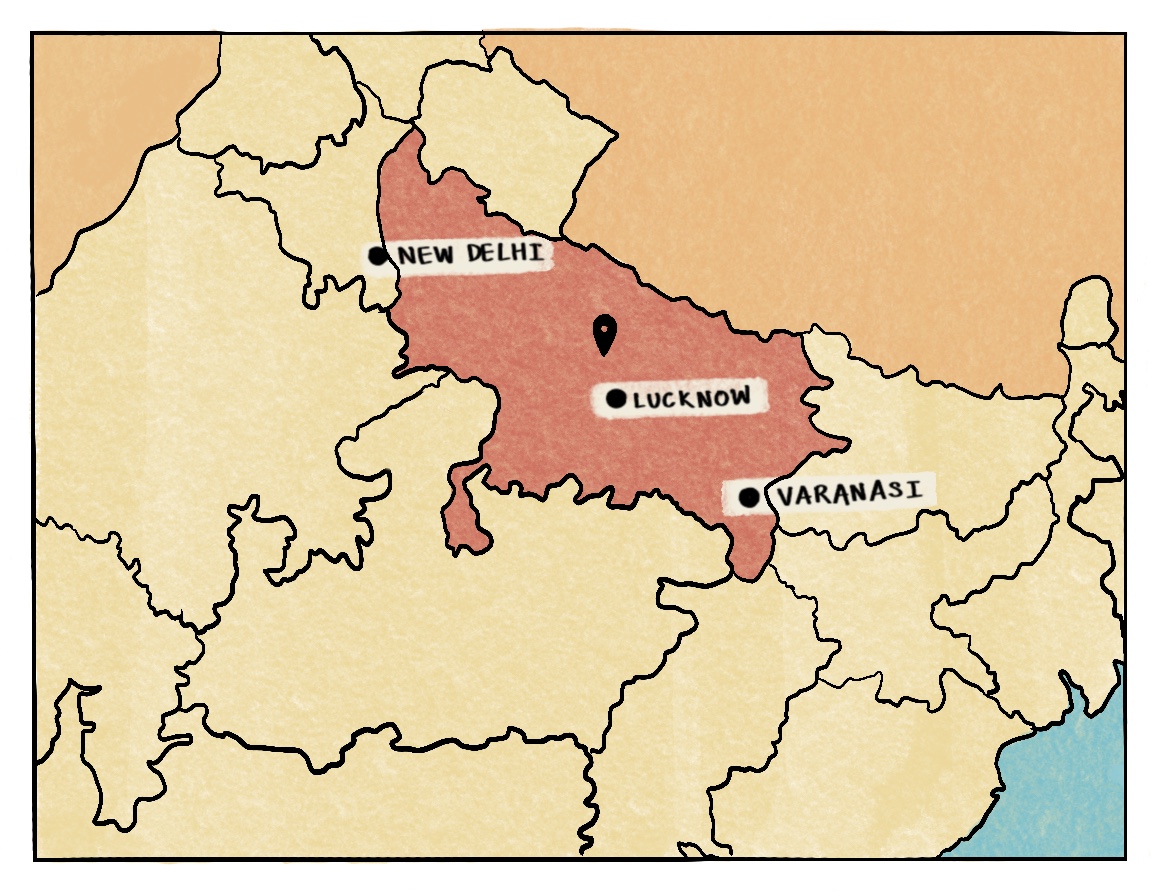

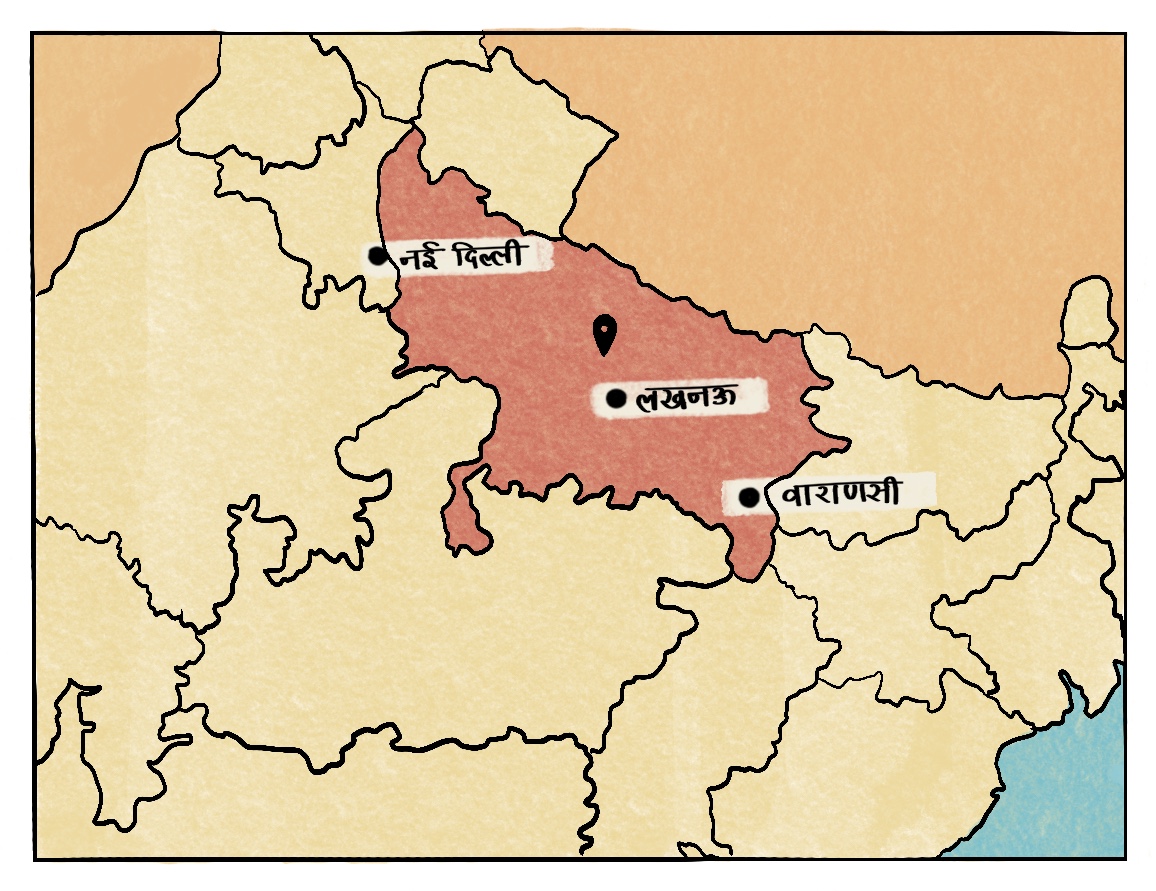

Well into the 1980s, the region of Sitapur (located in western Avadh, Uttar Pradesh, India) was famous across north India for its dals (pulses). Flanked by the Gomti and Sharda rivers and dotted with wetlands, Sitapur district was a major producer of urad (black gram), arhar (pigeon pea), masur (lentil) and chana (gram) as well as groundnuts. Not only were these nutritious foods sent across the country along the railway network, they were also an integral part of local diets, even of the most marginalised.

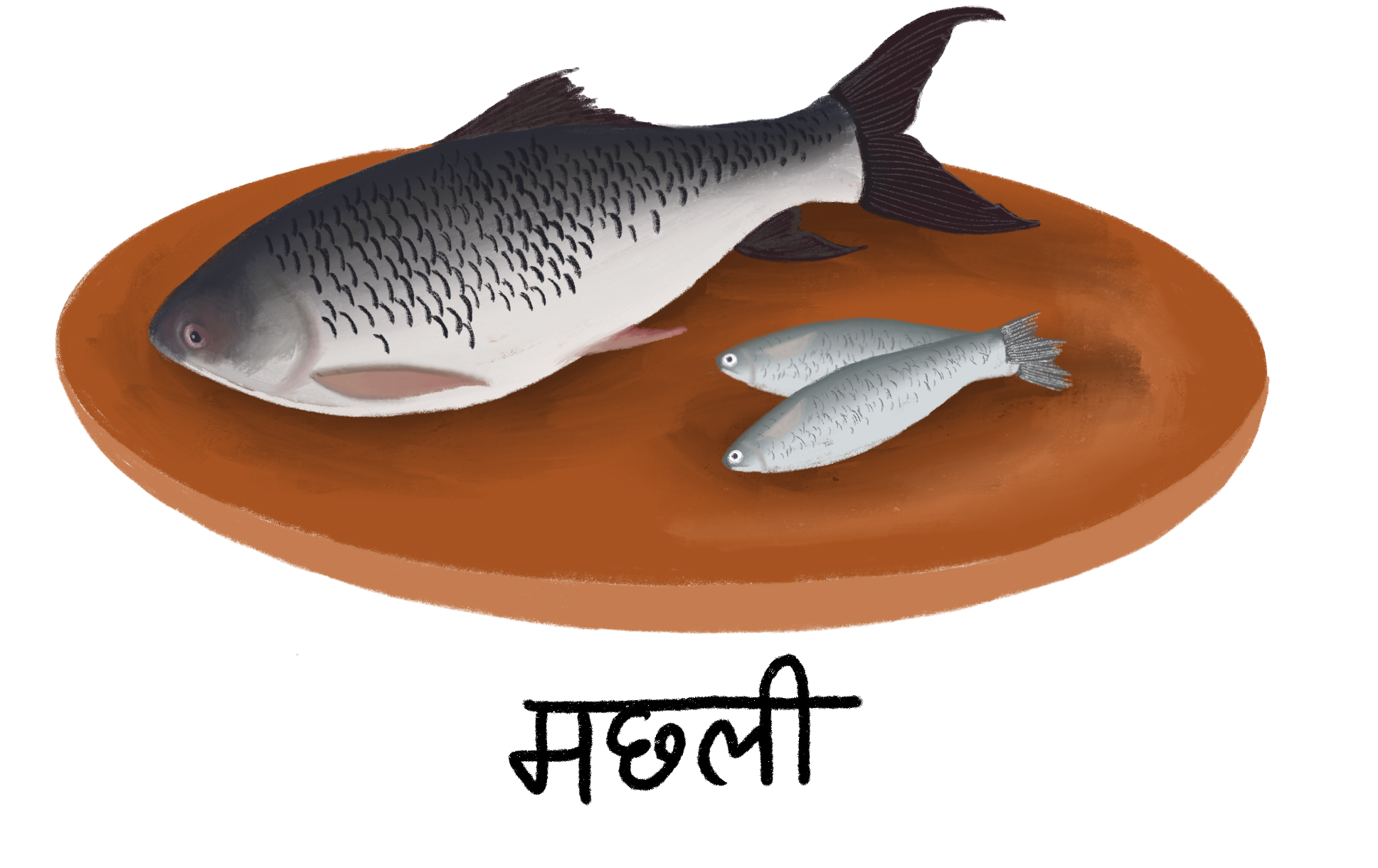

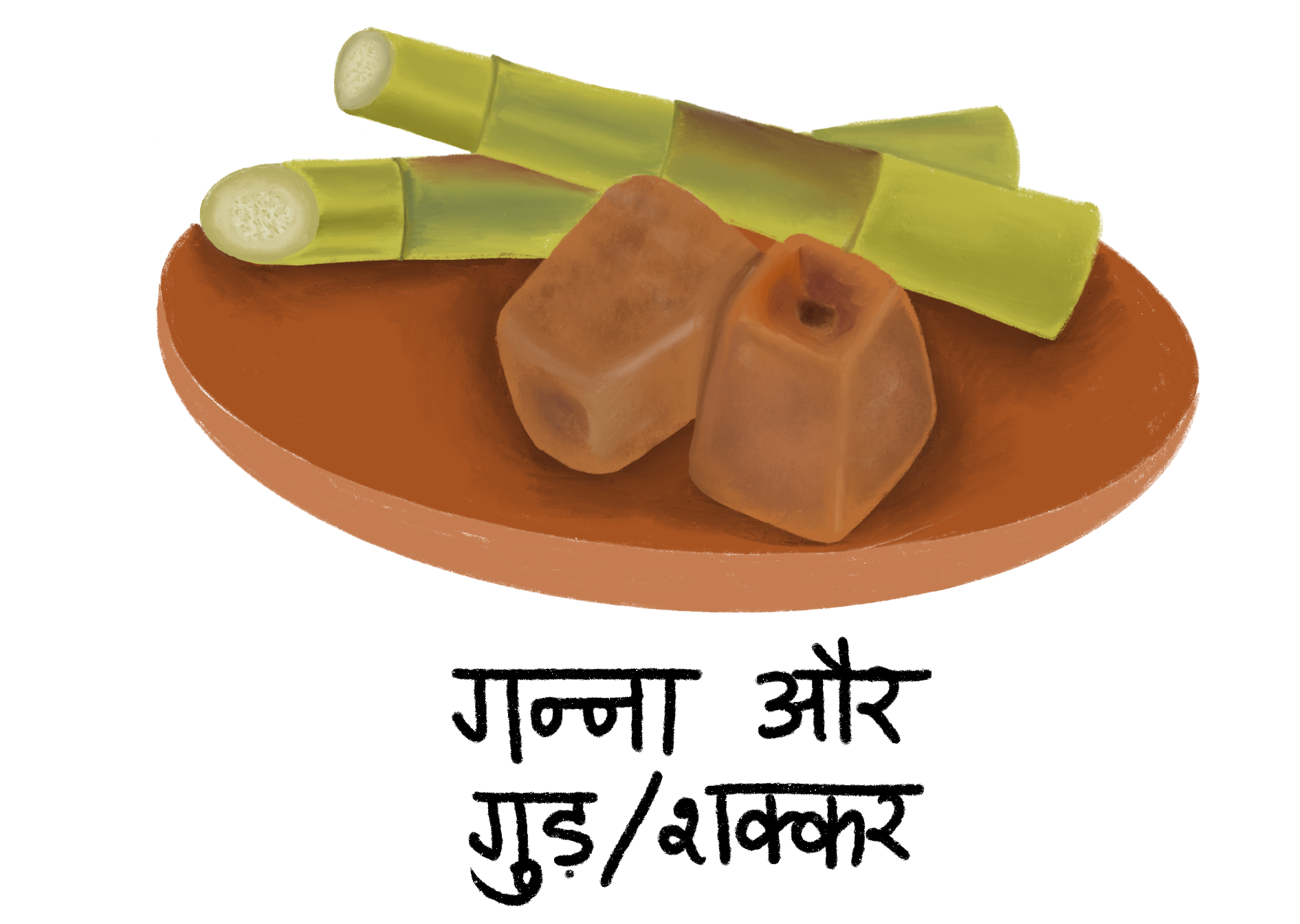

Along with these protein rich foods, diets included jaggery (high in iron and micronutrients), milk and ghee (clarified butter) for the rich and raab (liquidy jaggery) along with buttermilk (byproduct of the butter-making process) for the poor. Nutritious cereals like barley, bajra (pearl millet), dhaani (indigenous red rice) and husked millets (barnyard, kodo and foxtail) were cultivated and consumed across caste and class, although elite households ate wheat and white rice. Several varieties of vegetables, greens and fruits were cultivated, and many that grew in the wild were collected. Animals – cattle, goats and pigs – were an integral part of the farming system, and bred for milk or meat. Wild rice, fish, mushrooms, wild animals, tubers and other wild foods were hunted or collected from forests, wetlands and fallow fields and formed an integral part of food cultures. Diets changed with the seasons, and festivals marked these changes through ritualised consumption of seasonal foods.

You will be able to hear or read about some of these dietary practices as you browse specific items on the food mat.

Today, very few of these foods can be found growing in the region and they have also disappeared from people’s plates. In the past 40-50 years, changes in the agrarian landscape and the availability of packaged foods have transformed diets, and this has had a serious impact on household nutrition.

The ‘Recovering Food Narratives’ repository draws from a research study on food, farming and nutrition conducted by academics from IIT-Delhi in partnership with activists and farmer-labourers from Sangtin, a local collective. From these findings, a portal was conceptualised and developed in partnership with IIIT-Bangalore and Design Beku.

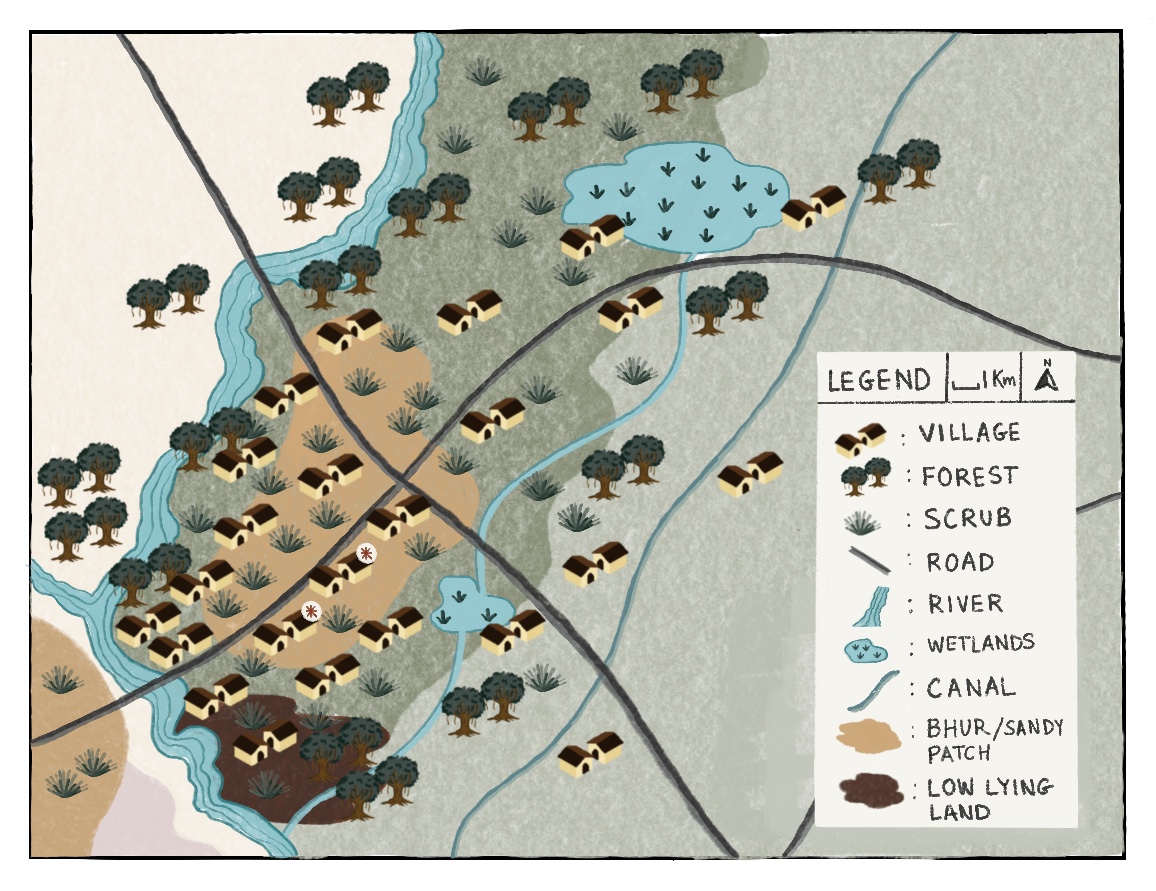

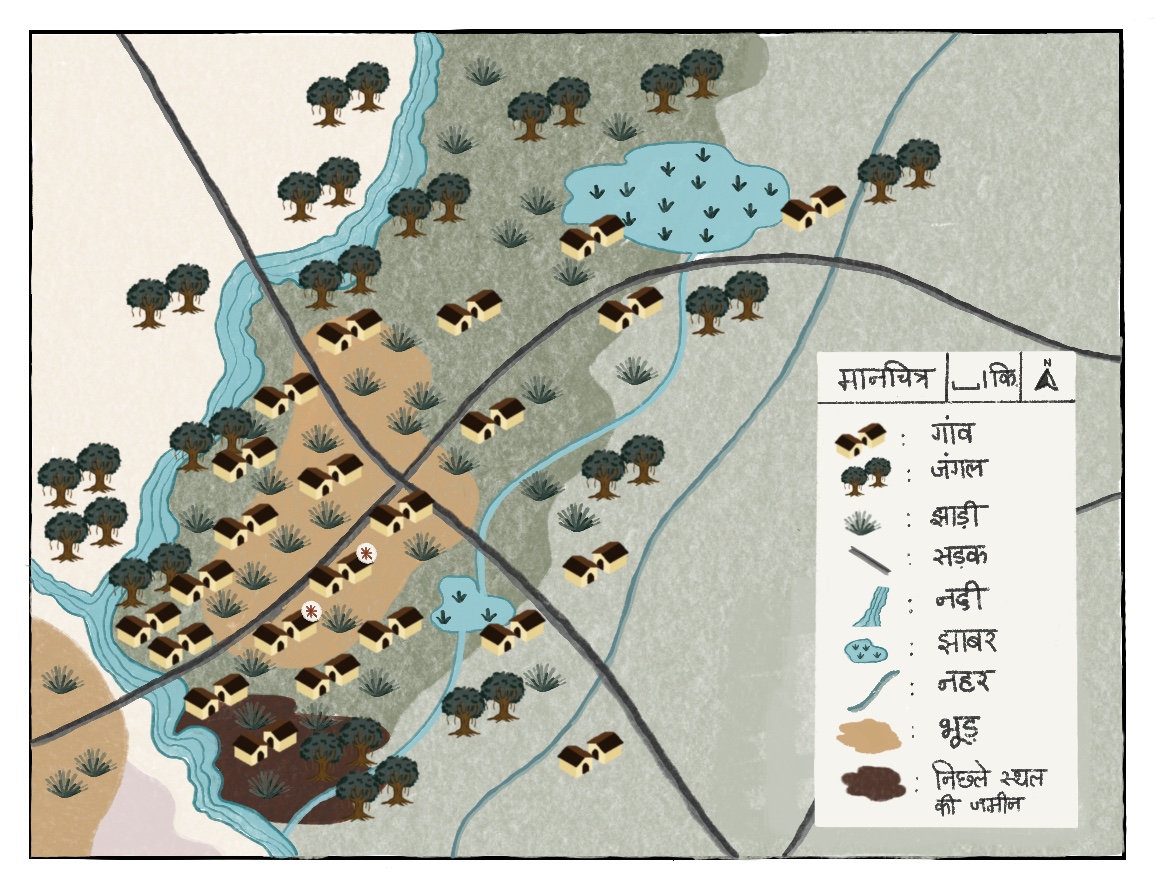

The field research team conducted a multi-season food consumption survey of 102 families (selected to represent caste and class heterogeneity) in 2 villages to gain insights into current diets. Further, we conducted 27 focus group discussions, mainly with elderly villagers in 24 villages across the region (see map), along with oral history interviews with some of the respondents. We also interviewed over 100 farmers, traders, processors, retailers, government officials, academics and local leaders to understand the history of various food commodities that were part of local, regional and national supply chains. This information was triangulated using historical accounts of the region (going back to the pre-colonial period), district-level agricultural data and secondary material on food and farming.

We found that as cropping patterns changed, freely available foods were lost or became commodified, and thus diets were transformed. Government policies and interventions not only expanded monocropping of Green Revolution crops, they also facilitated the conversion of ‘wastelands’, wetlands and other diverse commons into cultivated monocropped fields. The penetration of packaged foods along with people's perceptions of certain foods as ‘cultured’ and modern also drove the change (e.g. wheat replaced millets, white sugar replaced jaggery, biscuits and chips replaced home-made millet snacks).

Past diets were diverse and rich in macronutrients and micronutrients such as protein (dairy products, pulses, meat and fish) and iron (greens, oilseeds, meat). However, current diets mainly consist of processed carbohydrates and are severely deficient in protein, micronutrients and fibre. This dietary transition has had serious negative consequences. During our consumption survey, the respondents were weighed and underwent a blood test. High levels of anaemia and low BMI were recorded for both men and women. The low weight of young women and men were of particular concern.

We also found that while hunger existed in the past, it was shaped by caste, class and social position. Not everyone was hungry. Marginalised groups suffered from seasonal deprivation because they lacked access to resources, especially fertile land, which was unevenly distributed. These inequities date back to the colonial period, when the British gave the landlords unprecedented rights, and pushed various communities into agriculture while demeaning hunting and pastoral lifestyles. Gender was, and continues to be, a major factor in dietary deprivation, with women not only suffering from lower access to food, but also self-regulating their consumption, especially of meat.

We hope that our findings about past and current diets, plus our subsequent discussions and interventions will help us find ways out of this nutritional crisis.

खेती और खान पान में बदलाव

पिछले कुछ वर्षों में सीतापुर जिले में बढ़ते कुपोषण को देखते हुए, संगतिन और आई. आई. टी. दिल्ली ने मिलकर खेती खाना और पोषण के बीच रिश्तों को समझने की कोशिश की। इस शोध में हम 2 गांव के 102 परिवारों से (जो विभिन्न जाति और वर्ग से थे) चार मौसमों में मिले और उनके खान-पान का सर्वे किया। इससे पता चला कि अधिकतर लोग सिर्फ गेहूं की रोटी, सफेद चावल, चीनी, आलू, चाय और बाजारी पदार्थ, जैसे बिस्किट और रस्क, खा रहे है, जिससे उनके पोषण की जरूरतें पूरे नहीं हो रही हैं।

हम जानते थे कि यह क्षेत्र, पश्चिमी अवध, कभी दालें और मूँगफली के लिये मशहूर हुआ करता था । देश भर में पहुँचती थी सीतापुर की उरद, अरहर और मसूर की दाल। दाल मिलों के साथ-साथ मूंगफली का तेल भी कारखानों में तैयार हो कर उत्तर भारत में कई जगह पहुँचता था। यहा लोगों के खान-पान में दाल, मूंगफली, गुड़, मोटा अनाज प्रमुखता से था। सर्दियों में गाँव में गुड़ बेल और भुर्जियों के ठेले, गर्मियों में आम और अमरूद के बगीचे, बरसात में हरा साग, मशरूम और मछलियाँ, हर मौसम में कई प्रकार की खाद्य सामग्री हुआ करती थी। ढेरों त्योहार अलग-अलग मौसम में उगने वाले फसल से जुड़े थे। अब हमारे सामने कई सवाल आये जैसे - कहाँ गई सारी विविधता, कहाँ गया पोषण? इनके गायब होने के क्या कारण रहे होंगे? इन सवालों के कुछ जवाब हमें शोध के दूसरे हिस्से से मिले।

यह शोध आई आई टी दिल्ली और संगतिन, सीतापुर ने मिलकर किया है और यह पोर्टल आई आई आई टी बेंगलुरू और डिजाइन बेकु के साथ मिलकर बनाया गया है।

हमने 27 ग्रूप चर्चा के माध्यम से कई लोगों से, खास कर बुजुर्गों से, बात की जिससे क्षेत्र के पुराने कृषि पद्धति, खान-पान और इनमें बदलाव के बारें में समझे। इनमें से कुछ जानकार लोगों से लम्बी बातचीत हुई, और साथ में 60 से ज्यादा किसान, व्यापारी, सरकारी अधिकारी,उद्योगपति और सीतापुर के कुछ जाने माने लोगों से बात चीत हुई। हम उन सब लोगों का आभार प्रकट करते हैं जिन्होनें अपना समय दिया और अपने अनुभव हमसे साझा किए। जो जानकारी लोगों से मिली, उसे किताबी जानकारी से भी जोड़ा गया – जैसे ऐतिहासिक खाते, जिला-स्तरीय कृषि डेटा और साहित्य समीक्षाएं। इन सब प्रक्रियाओं और जुड़ी समझ को हम इस पोर्टल के माध्यम से साझा कर रहे हैं।

ऐतिहासिक खान पान विविध था और पोषण से भरपूर था। मौसम के अनुसार अनाज, दलहन, तिलहन, फल, साग, सब्जी, दूध या दुग्ध पदार्थ लोगों के भोजन का हिस्सा थे। मोटा अनाज (millet) जो आज पौष्टिक भोजन कहलाता है, खान-पान का अहम हिस्सा था। कई जातियाँ मछली, छोटे जानवर (जैसे चौगड़ा), पक्षी, सुअर और अन्य अलग-अलग प्रकार के मीट खाते थे। जंगल, झाबर, खेत और परती जामीन से बटोरी हुई कई पौष्टिक चीजें लोगों के खान पान का हिस्सा थीं।

पहले भूखमरी भी थी, लेकिन सभी इससे त्रस्त नहीं थे। कुछ दलित जातियाँ, जिनके पास उपजाऊ जमीन नहीं थी, और जो दूसरों के यहाँ अनाज के बदले मजदूरी करके गुजारा करते थे, वे हैवत (जाड़े) में खास तौर से भूख से जूझते थे। यह इसलिए क्योंकि खरीफ की फसल चुक जाती थी, ठंड परेशान करती थी और काम मिलना मुश्किल था। भादों-कुंवार (अगस्त-सितम्बर) में भी थोड़ा कष्ट होता था क्योंकि उस समय रबी के अनाज खत्म हो जाते थे। अंग्रेजों के समय जमींदारों को जमीन का पूरा हकदार बनाया गया, और कई जातियों के छोटे किसानों को कुछ नहीं मिला। साथ ही अंग्रेजों ने खेती को बड़ा स्थान दिया, और पशु-पालन व शिकार से गुजारा करने वालों को कमतर माना। यही असमानताएँ भूखमरी के मुख्य कारण थे। औरतें भूख से अधिक जूझती थी क्योंकि सामाजिक मान्यताओं के अनुसार वह सबसे आखिर में खाती थी और अक्सर बचा-खुचा ही उनके हिस्से आता था। हाँलाँकि यह स्थितियाँ आज भी अधिकांशतः देखने को मिलती है।

आज़ादी के बाद जमींदारी उन्मूलन और भूमि सुधार अधिनियम के तहत जो किसान जोतकार थे, उनको जमीन का हक मिला। यह ज्यादातर सवर्ण और पिछड़े जातियों के थे। 1970के दशक में 'गरीबी हटाओ' अभियान के चलते हुए कई भूमिहीन किसान, जो ज्यादातर दलित थे, जमीन के हकदार बनें। यह जमीन आमतौर पर गाँव में सबसे कम उपजाऊ जमीन थी, जैसे कि ऊँची-नीची (जिसे अवधी में ऊबड़-खाबड़ कहते है), बलूई या निचली जमीन। गरीबों को उत्तम जमीन दिलाने की बजाय, सरकार ने इन जमीनों को मेडबन्धी, सम्तलीकरण इत्यादि से खेती के योग्य बना दी। हाँलाँकि यह वहीं जमीने थी जहां से गरीब परिवार खाना बटोरते थे। जंगल, झाबर, पड़ती जमीन सब खेत बन गए।

हरित क्रांति की तकनीकों से, सरकार की योजनाओं से और बाज़ारिकरण के आने से पुराने खाने के स्त्रोत खत्म हो गए। जैसे खेतों में मोटा अनाज, दलहन और तिलहन की जगह गेहूं, धान और गन्ने ने ले ली। दूध के बाज़ारीकरण से दुग्ध पदार्थ जैसे मट्ठा मुफ़्त में मिलना बंद हो गया। पहले यह बड़े किसानों से गरीब परिवारों को दे दिया जाता था। अब ऐसा नहीं होता है। बाजार में दालें महंगी हो गईं पर बिस्कित, चिप्स, पेप्सी/कोला आदि सस्ते मिलने लगे। ऐसे हालत में खान पान तो बदलना ही था।

सवाल यह है कि क्या सिर्फ सरकार और बाजार इसके जिम्मेदार हैं? हमारे शोध से यह भी पता चला कि कई पौष्टिक खाद्य पदार्थ जैसे मोटा अनाज, गुड़, बटोरा हुआ खाना आदि गरीबों का खाना माना जाता था। मजबूत जातियाँ गेहूं खाती थीं और कमजोर जातियों को गेहूं उगाना तक मना था। हरित क्रांति ने एक तरह से सबको इस मामले में बराबर कर दिया - हर एक को गेहूं नसीब हो गया। लेकिन साथ में गरीबों के थाली से दाल, मछली, मट्ठा आदि ग़ायब हो गए। बाजारी खाने का प्रचलन भी ऐसे ही बढ़ा। सफेद चीनी, बिस्किट, पेप्सी आदि खाने का हिस्सा बन गए। आधुनिकता की मार ने गरीबों की मिठाई (गुड़) की हालत खराब कर दी। अब गुड़ सिर्फ शराब बनाने के लायक रह गया। वही गुड़ जिसमे भरपूर मात्रा में आयरन और कई विटामिन हैं। यह दुर्भाग्यपूर्ण हालत ही कही जायेगी।

कई ऐतिहासिक खाने अब मिलते ही नहीं हैं, जैसे सनई के फूल या चना पटापर, और कई खानों को बनाने की विधियाँ भी लोग भूल गए हैं।

गायब हो गये हैं पोषण को बढ़ाने के आसान रास्ते....

यह पोर्टल इन भूले बिसरे खाद्य सामग्रियों और उनसे जुड़े लोगों के अनुभव और उनकी यादों को दोबारा ताज़ा करने की एक कोशिश है। अगर इस से हम अपने खान-पान के बारे में और गहराई से सोचने पर मजबूर हो जाएँ जैसे - हमारा भोजन कहाँ से आ रहा है, इसको बनाने में प्रकृति का दोहन हो रहा है क्या, इस से हमारी सेहत पर क्या असर पड़ रहा है, किसान और ग्रामीण लोगों के क्या हालात हैं - तो हमारा शोध और इस वेबसाईट का बनना सफल होगा।